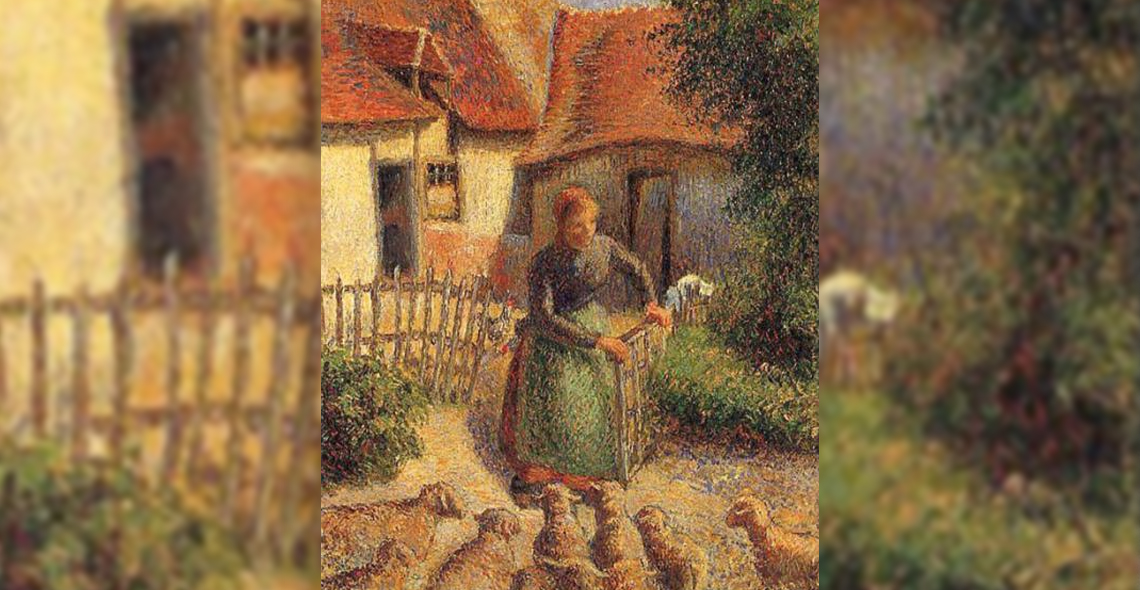

A recent article by Le Monde tells us about the thwarted destiny of a painting by the Impressionist Camille Pissarro: “La Bergère rentrant des moutons”. Spoliated from the Meyer family by the Nazis during the occupation of France, the painting was acquired in 1957 by the American couple Weitzenhoffer, who bequeathed it in 2000 to the Fred Jones Jr. Museum at the University of Oklahoma.

The heiress of the Meyer family, Mrs. Léone-Noëlle Meyer, has been fighting since 2012 to have the painting returned to France. She has reached an agreement with the Fred Jones Jr. Museum, in 2016, to ensure the restitution of the painting to her, in exchange for a perpetual rotation of the work between this museum and a French institution, in this case the Musée d’Orsay. While the painting is due to return to the United States in 2021, Léone-Noëlle Meyer is fighting to denounce this agreement, which she assures she signed in haste and at a distance. A clause in the agreement obliging Mrs. Meyer to bequeath the painting to a French institution, which will have to accept the principle of rotation of the work, proves to be very restrictive in the long term. The institution that will be receiving the masterpiece will have to bear part of the costs of transporting the work, transforming this superb impressionist painting into a poisoned gift.

In 2016, Mrs. Meyer has chosen to opt for what is known as an alternative dispute resolution or ADR. These ADRs are resolution processes mostly conducted outside of the court system, such as arbitration, negotiation or mediation. They are regularly used in cases involving the restitution of cultural property, as they make it possible to avoid lengthy, costly and uncertainly-ended lawsuits. They also guarantee, for each party, a certain level of confidentiality.

But, as we saw in the case of “La Bergère rentrant des moutons”, they do not always guarantee a satisfactory agreement in the long term. These alternative dispute resolutions can also have adverse effects, as Lynda Albertson, CEO of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art, writes, referring to recent restitution cases in Cambodia, Egypt and Iraq: “As regards both of these restitutions I would ask these individuals why, with these grand gestures of reconciliation, did neither party turn over the purchase and sale records for these objects. Something which would truly make reparations as doing so would allow illicit trafficking researchers and law enforcement investigators to trace and return other pieces of history handled by the individuals responsible for engaging in these two unseemly debacles“. Indeed, settling privately disputes regarding the ownership of a cultural good can also serve as a way to disseminate its illegal origin. In Mrs. Meyer’s case, the painting was included in the French repertoire of looted and non-returned works, created as early as 1947, which makes the circumstances of its successive acquisitions questionable.

If ADRs are increasingly used in the business world, and not only in the case of the restitution of cultural property, it is because they offer definite advantages, avoiding the pitfalls of legal proceedings. However, they can also overlook a work of art’s murky past and turn it into a financial burden that is difficult for the recipient to bear.

[Image: « La Bergère rentrant des moutons », Camille Pissarro, 1886]